“US recognition of severed Kosovo province was a serious mistake, leading to an escalation of tensions, instead of calming down the situation in the Balkans … consensus boils down to the fact that nobody knows where Kosovo is” (John Bolton)

“The recognition of Kosovo was premature and conditioned by great pressure from the former American administration”… “Today, we can see that two-thirds of the international community does not recognize Kosovo … this shows that we are talking about a grave mistake” (Gerhard Schröder)

Two years has gone since Kosovo Albanians declared their independence from Serbia. However calling to Kosovo needs country code 381 – which is Serbia – or by GSM 377 44 (via Monaco Telecom) or others via Serbian operators. This because as at this time, Abkhazia, Kosovo, Transnistria, Somaliland, South Ossetia and others are not in the ISO 3166-1 standard due the absence of recognition by the United Nations. Situation is one minor example about Kosovo “statehood”. Besides formalities – like that the province is administrated as international protectorate by foreign powers – the on the ground status is more complicated and even going more far away from drawing board ideals of Washington and Brussels.

Two years has gone since Kosovo Albanians declared their independence from Serbia. However calling to Kosovo needs country code 381 – which is Serbia – or by GSM 377 44 (via Monaco Telecom) or others via Serbian operators. This because as at this time, Abkhazia, Kosovo, Transnistria, Somaliland, South Ossetia and others are not in the ISO 3166-1 standard due the absence of recognition by the United Nations. Situation is one minor example about Kosovo “statehood”. Besides formalities – like that the province is administrated as international protectorate by foreign powers – the on the ground status is more complicated and even going more far away from drawing board ideals of Washington and Brussels.

Those who supported Kosovo independence said that Kosovo was unique case and not precedent thousands of ethnic or separatist movements around the world made other conclusion – Abkhasia and South Ossetia came first from the “Pandora box” which Kosovo opened. To limit the degree of damage it is time to restore international forums and law.

Those who supported Kosovo independence said that Kosovo was unique case and not precedent thousands of ethnic or separatist movements around the world made other conclusion – Abkhasia and South Ossetia came first from the “Pandora box” which Kosovo opened. To limit the degree of damage it is time to restore international forums and law.

Legal aspect

From legal aspect the Nato bombings and later orchestrated unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) of Kosovo Albanians were against international law and violation of the UN Charter, Helsinki Accords and a series of UN resolutions including the governing UNSC resolution #1244. Officially Kosovo is international protectorate administrated by UN Kosovo mission. Now the case (UDI) is in International Court of Justice and its statement is expected Mid 2010. (More “UN is sending Kosovo case to ICJ”).

Whatever – depending point of view – status Kosovo has, the province is de facto administrated by international community. However the administration is still in full chaos because there is administrators more than enough. 1st (not order of authority) we have European Union Special representative (EUSR) who is double hatted as chef of International Community Office; 2nd we have Head of EU Commission liaison office; 3rd we have EULEX mission; 4th there is KFOR troops including Europe’s second largest Nato base, 5th international administrator is from UN side – SRSG as Head of UNMIK mission. All these administrators and other supervisors like OSCE, Quint etc – are playing in the same sandbox wondering who is doing what and where. In addition in Kosovo is also local stakeholders like separatist governments institutions in areas habitat by Albanians and parallel Serb institutions in areas habitat by Serbs. (More e.g. in (“EULEX, UN and mess-up in Kosovo” )

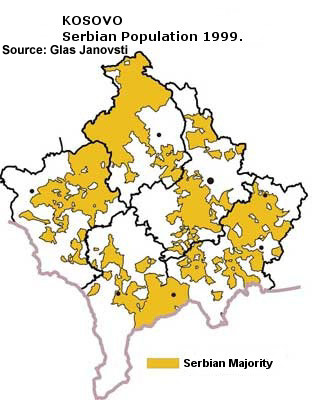

The fact on the ground is that northern part of Kosovo is integrated to Serbia like it always has been, as well those pats south of Ibar river, which are not ethnically cleansed by Kosovo Albanians. Between ethnic groups a huge operation of international community is going on with its foggy ideas.

Refugees and unrealized returns

The refugee and IDP (“internally displaced persons”) question is of paramount importance in Balkans. In Serbia the refugee problem came when Serbs were expelled from East Croatia and Croatian Krajina. The IDP problem is a follow-up of Kosovo conflict when some 200.000 Serbs and some thousands of Roma were expelled from there to northern Serb-dominated part of province or to Serbia. During Nato bombings also Kosovo Albanians – about 700.000 – escaped from the province but most of them have returned back. Most of Montenegro refugees – 16259 – fled from Kosovo. Nearly all of Serbia’s IDPs fled also from Albanian majority parts of Kosovo province. Despite EU’s nice ideas about multi-ethnic Kosovo and implementation of housing and other return programs only a fraction (few per cent) of Serb IDPs have returned to Kosovo after ten years of international administration while majority of Kosovo Albanian refugees returned during last half of year 1999.

To table below I have collected the numbers of refugees and IDPs in western Balkans; the sum total includes also asylum-seekers, stateless etc. persons. As source I have used UNHCR report 16thJune 2009 and “Internal Displacement in Europe and Central Asia” report made by UNCHR and The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), established in 1998 by the Norwegian Refugee Council.

| Country | Refugees | IDPs | Total |

| Albania | 65 | 0 | 87 |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | 7257 | 124529 | 194448 |

| Croatia | 1597 | 2497 | 33943 |

| (FRY) Macedonia | 1672 | 0 | 2823 |

| Montenegro | 24741 | 0 | 26242 |

| Serbia | 96739 | 225879 | 341083 |

The table above is maybe surprising to those who have the picture – made by western mainstream media – in their minds, that (only) Serbs were making ethnic cleansing. In reality today the Serbs are the biggest victims of Balkan wars. (More in my article “Forgotten Refugees – West Balkans”).

Failed post-conflict reconstruction

The new report made by Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gives a bare picture about worsening situation of minority rights in today’s Kosovo. Instead to return to their homes after ethnic cleansing implemented by Kosovo Albanians after Nato intervention 1999 minorities are beginning to leave Kosovo, because they face exclusion and discrimination.

One of the cruellest example of failed post-conflict reconstruction is the case of Roma children living in UN camps in North Mitrovica, Kosovo. So far 81 has already dead after ten years suffering in United Nations Camps for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs), living in place which is described the most toxic site in Eastern Europe. Their case gives another perspective related to “humanitarian intervention” implemented by Nato and to international administration implemented afterwards and backed with billions of Euros EU financing. (More in my article “UN death camps, EU money, local negligence”)

Despite huge EU programmes and reports singing their praises the progress in Kosovo has been modest if not non-existing. Kosovo faces major challenges, including ensuring the rule of law, the fight against corruption and organised crime, the strengthening of administrative capacity, and the protection of the Serb and other minorities. EU Commision’s 2009 progress reports of Kosovo province and its neighbours can be found as pdf from my Document library.

The focus of international state-building efforts in Kosovo has been

Kosovo highlights the fact that states and international organisations intervening in post-conflict situations should be realistic about what socio-political change they can actually achieve. Despite huge resources and strong mandate international administration can fail if the situation analysis is combination of false supposition and actions based to high flown drawer desk plans. The state-building process can also cease due pressure. This was evident in Kosovo when the eruption of violence in March 2004 pushed the international community towards addressing the status question and throw earlier “standards before status” principle to litter box. (More e.g. in “Pogrom with Prize”)

Insignificant economic base and remarkable social challenge

Official statistics from year 2008 shows that export from Kosovo amounted about 200 millon Euro while import increased to 2 billion Euro, which makes trade balance almost 1,800 million Euro minus. If export is covering some 10 percent of import so from where is money coming to this consumption. The estimate is that when export brings mentioned 71 million Euro the organised crime (mainly drug trafficing) brings 1 billion Euro, diaspora gives 500 million Euro and international community 200 million Euro.

In 2007, more than 40 percent of contributes to direct tax revenues and sustains the delivery of public services Kosovo’s GDP was made up of foreign assistance, remittances and foreign direct investment – mostly privatisation proceeds and the issuing of a second mobile phone licence. All of these outside contributions are likely to decline substantially as a consequence of the global financial crisis, with dire consequences for Kosovo’s budget.

Kosovo has Europe’s youngest and fastest – growing population. Yearly 30,000 more young people enters working age than the number that leave labour markets which due Kosovo’s poor economy can not absorb them. Same time the education system is poorly governed, poorly resourced, and prone to corruption. Hardly any of the 30 private universities in Kosovo, for example, have met accreditation criteria (BritishAccreditationCouncil2008), and with few exceptions they provide sub-standard education. This leaves a whole generation of Kosovars without marketable skills and with very limited economic perspectives – at least legal ones.

The poor state of Kosovo’s economy combined to demographic challenge is likely to fuel a range of security threats, such as illegal trafficking, migration, and organised crime.

Organised crime

Links between drug trafficking and the supply of arms to the KLA (Kosovo Liberation Army) were established mid-90s. In West KLA was described as terrorist organization but when US selected them as their ally it transformed organization officially to “freedom” fighters. After bombing Serbia 1999 KLA leaders again changed their crime clans officially to political parties. This public image however can not hide the origins of money and power, old channels and connections are still in place in conservative tribe society.

In some other important drug transit zones trafficking is reflected in high levels of violence but not in Balkans. UN report explains this that good links between crime organizations and commercial/political elites have ensured that Balkan organized crime groups have traditionally encountered little resistance from the state or rival groups. To keep fragile situation calm (western) international community don’t interfere criminal activities leaded its former allies.

In some other important drug transit zones trafficking is reflected in high levels of violence but not in Balkans. UN report explains this that good links between crime organizations and commercial/political elites have ensured that Balkan organized crime groups have traditionally encountered little resistance from the state or rival groups. To keep fragile situation calm (western) international community don’t interfere criminal activities leaded its former allies.

The real power in Kosovo lays with 15 to 20 family clans who control “almost all substantial key social positions” and are closely linked to prominent political decision makers. German intelligence services (BND) have concluded that Prime Minister Thaçi is a key figure in a Kosovar-Albanian mafia network. Two German intelligence reports – BND report 2005 and BND-IEP report Kosovo 2007 – are giving clear picture about connection between politics and organized crime; both reports can be found from my document library under headline Kosovo.

I have earlier described circumstances in Kosovo with “Quadruple Helix Model” where government, underworld, Wahhabbi schools and international terrorism have win-win symbiosis. (More in “Quadruple Helix – Capturing Kosovo”) In general there is expectations that Kosovo is sliding to be a “failed state” I am however tending to the opinion that a “captured state” is better definition.

War crimes

The present day circumstances are shadowed also by the fact that most of the war crimes committed 1999 are still unsolved. On the other hand the situation declares null and void the efforts for multi-ethnic society, on the other hand it prevents transformation of Kosovo-Albanian political field from tribe level more democratic practice. For today’s politicians war crimes are important to keep non-existing due the imago reasons or because they now are part of regular (illegal) business. Occasionally some details pop up like it was case with organ trafficking (More in “New Cannibalism in Europe too?”)

The actions of the Nato campaign 1999 are quite well documented but despite bombings were against international and war crimes committed no trials has been made. Nato planes destroyed 4 % of its military targets during bombing – partly because for avoiding own casualties they launched missiles so high that could not make difference between wooden decoys and real weapons. Instead of military targets the main damage was made against civilian targets such as destroying an embassy (China), a prison (Istok), three column of Albanian refugees (81 dead March 13th and 75 April 14th), radio-tv station (Belgrade, 16 civilians dead), a passenger train (Grdelica bridge, 14 dead), also a number of infrastructure, commercial buildings, schools, health institutions, cultural monuments were damaged or destroyed. Some 2.500 people (mostly civilians) were dead, material civil infrastructure damage is estimated to be some 30 billion dollars. (More e.g. in “10th anniversary of Nato’s attack on Serbia”)

April 14th), radio-tv station (Belgrade, 16 civilians dead), a passenger train (Grdelica bridge, 14 dead), also a number of infrastructure, commercial buildings, schools, health institutions, cultural monuments were damaged or destroyed. Some 2.500 people (mostly civilians) were dead, material civil infrastructure damage is estimated to be some 30 billion dollars. (More e.g. in “10th anniversary of Nato’s attack on Serbia”)

Kosovo is still suffering of some consequences of Nato’s 1999 bombings such as the effects of the use of depleted uranium (DU) on the civilian population. The Nato allegedly used shells with depleted uranium which are still today causing an increase in the number of cancer patients. (More from article “Use of Depleted Uranium proved in Nato bombings”)

Epilogue

The outcome today in Kosovo is a quasi-independent pseudo-state with good change to become next “failed” or “captured” state if international community does not firm its grip in province. Today’s Kosovo is already safe-heaven for war criminals, drug traffickers, international money laundry and radical Wahhabists – unfortunately all are also allies of western powers.

From my viewpoint the only way to get sustainable solution to Kosovo is through real negotiations between local stakeholders. To get start of real talks US should freeze or withdraw its recognition of Kosovo UDI; otherwise it takes too long time for Kosovo Albanians to find out that some negotiated outcome ? be it cantonization, partition or whatever agreed – could be better than status quo. (About possible solutions “Dividing Kosovo – a pragmatic solution to frozen conflict” and “Cantonisation – a middle course for separatist movements“)

The readiness to open new talks over status question may be increasing. I quote Gallup

The latest Gallup Balkan Monitor survey conducted in September 2009 showed Kosovo Albanians are less positive toward independence. Seventy-five percent of Kosovo Albanians said independence was a good thing, down from 93% who said so in 2008. One in five Kosovo Albanians said they did not have an opinion. Furthermore, in 2009, 80% of Kosovo Serbs believed that independence was a bad thing, statistically unchanged since 2008.

When time runs so I think that more and more local population would like to un-freeze conflict and concentrate to issues that matters.

Of course if US wants keep one frozen conflict more in world and if EU is ready to squander more billions of euros for its capacity building efforts nothing needs to be done. (More e.g. in “Kosovo-update”)

[…] Kosovo: Two years of Quasi-state […]

[How apposite that you should quote from Gerhard Schröder, Vladimir Putain’s lapdog and traitor to Western civilization:

“a man is known by the company he keeps”

“Quasi-state”? You can’t even translate properly into English the Serb propaganda phrase “kvazidržava”.]

@Sebaneau

” How apposite that you should quote blah, blah, blah……..You can’t even translate properly into English the Serb propaganda phrase “kvazidržava””

Oh, that’s rich coming from someone who can’t write coherent English! What is your point? Ari is providing factual information that is completely neutral, fair and balanced.

Dear Nellie,

My original message was supposed to be in Finnish, and then you would have had an excuse for not understanding it. Unfortunately, Mr Rusila didn’t deem it fit to be published.

Yet, since you called it “incoherent” what didn’t you understand in the message I posted?

Was it “kvazidržava”?

That’s not English: that’s Serbian, and it means “pseudo-state”, not “quasi-state” like in Mr Rusila’s poorly translated propaganda.

Don’t you think a more clever person than you would have been able to understand what I meant? And to correct me if there was something wrong with the language?

To be sure, English is not my mother language. But to conclude that I must be wrong because it isn’t is a non sequitur (that’s latin for you) and a silly schoolyard taunt.

Taunt for taunt, let’s see your French now…

or for that matter your Albanian, Croatian, Serbian, Macedonian, Russian, Polish, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Danish, Norwegian or Finnish –all languages I have translated.

[…] Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state […]

[…] hear Mr. Nobel rolling in his grave? and his peace mediation methods: 500.000 bodies or sign! ja Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state ) Pelkkien konfliktien ratkaisu on mielestäni palokuntatoimintaa, tärkeää mutta toisarvoista. […]

[…] Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state […]

[…] jonka seurauksena suurin Balkanin pakolaisongelma on Serbiassa. Kosovon nykyisyydesta ks esim Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state ) Balkanilla on monia tarinoita etnisistä puhdistuksista eri ajoilta. 1990-luvun läntinen […]

[…] in criminal activity – including heroin trading – since before the 1999 war. More e.g in Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state and Captured Pseudo-State Kosovo […]

A truthful Serbians’ account on the blog of a lying Finn,

or “The World Upside Down”:

http://www.spiritofbosnia.org/current-issue/perceptions-of-serbia%E2%80%99s-elite-in-relation-to-the-dayton-agreement/

Perceptions of Serbia’s elitein relation to the Dayton Agreement

Sonja Biserko, July 2011; Spirit of Bosnia, October 2011, Bosnian Institute, 6 December, 2011

Introduction

Bosnia-Herzegovina (B-H) has been the central focus of the Serbian national project, not merely during the 1990s, but throughout the twentieth century. Serbia’s aspirations in B-H since the 1990s wars have remained consistent, and include the phased assimilation of Republika Srpska (RS). A section of the Serbian elite takes the firm position that

‘there is today no more essential and difficult task for the Serbian people as a whole than the preservation of Republika Srpska within the principles of the Dayton Agreement.’

In that respect, the political leadership of RS, and Milorad Dodik in particular, is viewed as ‘first-rate ….’ because that policy has at the same time ‘become a question of the defence of the truth’.

The war in Bosnia is treated by Serbian strategists exclusively as a fight for freedom on the part of the Serbian people; considerable energy, therefore, is invested in the fabrication of events which have the function of relativising responsibility for the war. Academician Dobrica Cosic, along with many others, is undoubtedly amongst the most active in promoting this approach. Whenever the opportunity arises he declares:

‘The fight for the truth about the past, for the truth about the Bosnian war; resistance to focusing on Markale and Srebrenica, arriving at the truth about the war which has been hidden by major world powers and Islamic factors… I think that RS is the last defence of Serbian truth, Serbian democracy and the Serbian right to survive.’

Milorad Dodik clearly has not formulated his policy without the support of Belgrade.

As Cosic confirms,

‘there is no stronger politician, no stronger or more respected person than Dodik in the defence of RS. I would say that he maintains and highlights our national honour. He is a man engaged in the active struggle against reactionary, anti-democratic forces, forces which are leading once again to conflict, and destroying the peace. He leads this struggle superbly, skilfully, and in a principled manner, and it is necessary to assist and support him in every respect, civil, intellectual, and political.’

War aims in Bosnia-Herzegovina

After its recognition by the international community on 6 April 1992, B-H was exposed to the most horrific political extermination of its Muslim population. The Serbs, within a very brief period of months from April to August 1992, seized 70 per cent of the territory of B-H.

This has been confirmed in numerous court trials at the Hague tribunal, in relation to Foca, Prijedor, Sarajevo, and so on. Many atrocities are yet to be investigated, particularly those which took place along the river Drina.

In that initial surge by Serb forces, Sarajevo in the space of a few days came under complete siege. The blockade of Sarajevo had already begun much earlier, in 1991. The army had become entrenched in positions around Sarajevo by the autumn of 1991, which also demonstrates that the military aggression against Bosnia was planned well ahead. The Serb population was prepared and armed.

Radovan Karadzic, already in October 1991, in preparing a plebiscite of the Serb people in B-H, declared: ‘you must assume power energetically and fully’ and

‘I say to you, whatever becomes of Bosnia, in Serb areas and villages not one Muslim foundation will be left unburied (…) The first foundation which is buried will fly in the air. The world will understand us when we say that we will not allow the demographic picture to be disturbed, either naturally or artificially. There is no chance of this, our territories are our territories, and even if we are hungry we will occupy them, for here it is a fight for life and death, a fight for living space.’

He then referred to difficulties with the international community, saying,

‘There will be foreign observers, everything will be observed, there will be criminal deeds other than purely ethnically-based ones because ‘we no longer need the old state structures for union which will cost us a million victims every 20 years, and the reconstruction of the state every 20 years in the name of our victims. There is no question about it. What is ours is ours’.

The wide-ranging preparations for aggression are evidenced by the speed with which the territory was seized, and the precision with which objects of historic and cultural value were targeted. The destruction of Bosnia’s cultural and historic heritage was deliberate and planned, with the aim, amongst other things, of destroying Bosnia’s multiculturalism.

Sarajevo had a specific place in the assault on B-H. Karadzic stressed that

‘…Sarajevo integrates Eastern Herzegovina and Romanija for us. Romanija has its marketplace in Sarajevo. Serbian Sarajevo is of inestimable importance’.

He went on to stress:

‘We can never abandon Sarajevo, because that would mean that only the Muslims had a good state, and they would smoke us out of three regions: Eastern Herzegovina, old Herzegovina and Romanija – nothing would remain there if we didn’t have our Sarajevo’.

The need to distract the international community (from the persecution of the civilian population and the atrocities carried out in other areas of Bosnia) was undoubtedly taken into consideration in the decision to lay siege to Sarajevo.

Until the spring of 1992, Belgrade had anticipated that B-H would remain in some form of union with Serbia. The situation in B-H was considered to be particularly difficult and fragile, because of the question of the three constitutive national groups, none of which had an absolute majority and none, consequently, could make a decision which was to the detriment of the others. This was the position Belgrade put before the world, thereby announcing war in the event of Bosnia becoming independent. ‘Separating B-H from Yugoslavia’ as Borisav Jovic put it, ‘is very dangerous and should not be undertaken’. He considered that the

‘best solution was for Serbia, Montenegro and B-H to be constituted as a new democratic Yugoslavia to ensure its continuity’.

The European Community decision to recognise Bosnia-Herzegovina’s independence and sovereignty was interpreted by Belgrade as the decisive error which led to escalation of the conflict. Jovic stressed that this was the fundamental cause of the conflict and suffering in B-H, not only for Muslims, but for the Serb and Croat people, too.

The launch of the RAM project in Bosnia was initiated by General Uzelac, who was responsible for its operation.

The war aims in Bosnia-Herzegovina were already very clearly articulated in the RS parliamentary session of May 1992.

Robert Donia, the American historian, in his expert witness testimony at the Hague Tribunal, identified six Bosnian Serb war aims.

The first was separation from the other two communities,

then the establishment of a corridor between Semberija (in the east) and Krajina (in the west); the third aim was the forming of a corridor along the Drina valley, to eliminate the Drina as a border between Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina;

the fourth war aim was establishing borders on the Una and Neretva rivers;

the fifth was the division of Sarajevo into Serb and Muslim parts,

and the sixth aim was an outlet for RS to the sea.

Reluctant acceptance of the Dayton Agreement

The Serbian elite accepted the Dayton Agreement under the pressure of reality, and in the knowledge that RS would otherwise be totally defeated.

The international community halted the Croatian-Muslim offensive which threatened the fall of Banja Luka and Prijedor, and a probable new exodus of Serbs from B-H. As SPO leader Vuk Draskovic emphasized at the time,

‘if the war had not been halted with the support of the major world powers, the whole of Republika Srpska would have fallen within a few weeks’.

Slobodan Milosevic in his contacts with the international community threatened that if that happened those [Bosnia’s] Serbs would be sent to Kosovo, which would generate a new conflict, which the international community would not be prepared for.

The international decision to accept the ethnic division of Bosnia and the war results, meant that, at the very outset, elements were introduced which could not guarantee a functional state. Regardless of Annex 7 (the return of refugees), whose application would at least in part ensure reconstruction of the prewar demographic picture of B-H, the Dayton Agreement, without a basic refugee returns policy, would not be able to secure consolidation of the Bosnian state.

Before the end of the Bosnian war, dissent arose between Belgrade and Pale in relation to the Owen-Stoltenberg Plan, which even led to Belgrade introducing sanctions and closing its border with RS in 1994. On the very eve of Dayton, Milosevic was forced to secure the support of relevant factors in RS, Serbia and Montenegro in order to be in a position to represent all Serbs in the forthcoming talks. The Agreement of 30 August 1995 guaranteed the position of the main negotiator on the Serb side, which all the relevant Serb leaders signed at the time.

Slobodan Milosevic considered the Dayton Agreement

as a new opportunity to present himself to Serbia and the region

as a peacemaker

The Serbian elites, on the other hand, did not accept the Dayton Agreement, as they considered that Milosevic had yielded under pressure, and that the Serbs had lost ‘ethnic’ territory in the Bosnian Krajina.

The Serbian Orthodox Church (SPC) synod was the most vocal of all in opposing the Dayton Agreement and, in an appeal to the international community, maintained that the signature of the Patriarch should be considered void.

Even the antiwar opposition in Serbia disapproved of the Agreement, essentially indicating that all parties were of the same view, fearing that Milosevic, under certain conditions, would gradually abandon Serbia’s objectives. DSS President Vojislav Kostunica expressed doubt that the Dayton agreement, as it stood, would not lead to further wars and instability. According to him,

‘the Serbian president from his room at Dayton ordered the Bosnian Serbs to congratulate Republika Srpska and wish peace and cooperation with the Muslim-Croat Federation. In other words, not in cooperation with the FRY, which meant that he had once again written them off and, with those congratulations, confirmed that they would live in another state’.

He further asserted that

‘if RS was formalized at Geneva, then the frontier between RS and the FRY was formalized at Dayton. This is the time, therefore, to consider strengthening the ties between RS and the FRY, which should be stressed in all plans.’

Vojislav Seselj stated that the so-called peace agreement signed at Dayton represented confirmation of the Serb defeat, and that

‘the Serb people will never be able to accept such hysterical anti-Serb policies as those of Milosevic and the international community as final, and a future democratic and nationally-oriented authority will certainly know how to fulfil the aspirations of our people to live in a united and strong Serb state.’

Slobodan Milosevic considered the Dayton Agreement as a new opportunity to present himself to Serbia and the region as a peacemaker. As he declared:

‘I am certain that this moment, this historic day, one might say, will mark a move towards peace, understanding and cooperation in the Balkans. It is time that all nations in the region move towards economic recovery, development, reconstruction and mutual cooperation’.

refugees were ‘created’ to demonstrate

that ‘life together was not feasible’

Refugees as an instrument for the creation of ethnic states

The negative attitude towards the Dayton Agreement rapidly shifted, once it was realized that this was the maximum achievable in the prevailing international climate, and that it was necessary to uphold the Agreement until such time as change occurred in the international context, so as to enable RS to secede from B-H.

In formulating that ‘waiting ’strategy, an important role was assumed by the round table entitled ‘The Serb nation in the new geopolitical reality’ (1997), when objectives and tactics became clearly defined: unification and freedom as a long-term strategic national aim. The starting-point was that the River Drina ‘remains to link the Serb people’.

The strategy was primarily defined in the policy of preventing the return of Bosniaks and Croats to RS. The refugee issue had an essential role in resolving the ‘Serb national question’. From the very start of the war, refugees were ‘created’ to demonstrate that ‘life together was not feasible’, while at the same time all non-Serbs were expelled from areas which were proclaimed as ethnic Serb territory. In that scenario, Kosovo could be divided with the Albanians on the basis of the model of territorial division carried out in Croatia and B-H: in other words, a massive ‘displacement of the civilian population’.

The exodus of Serbs from Croatia, and later from Sarajevo and Western Bosnia, was significant in the light of the plan to move Serbs to territory viewed as part of the new Serb state, namely RS.

The refugees best illustrate that the war aim of the Serbian regime was territorial conquest, and not exclusively the ‘unification of all Serbs’. That, amongst other things, was what Dobrica Cosic declared at the very outset of the war, when he asserted that

‘Serbs, with the fall of Yugoslavia, are compelled to find a state-political kind of solution to the national question. I see this in a federation of Serb lands. In that federation, it is necessary that not ‘all Serbs’ are included, but Serb ethnic lands.

In the above-mentioned gathering at Fruska Gora (1997), particular attention was paid to the form of the strategy towards Republika Srpska aimed at refugee return. It was confirmed at that time that:

(…) the main danger for the survival and prosperity of Republika Srpska was Annex 7 of the Dayton Agreement, that is, the Agreement on Refugees and Displaced Persons

(…) From the viewpoint of Serb national interests, that agreement was a double-edged sword. With its implementation the cohesive power of RS would be lost, and the role of those forces which seek to merge RS in a united state of B-H would be strengthened, and, even worse, the interests of the Serb people would be subordinated to those of the Muslims.

(…) From the viewpoint of Serb interests, RS is the one bright point in the process of SFRY disintegration. Yet, in the ensuing period, far greater pressure on RS and blackmail by the so-called international community – the strongmen of a new world movement – may be expected through implementation of the Annex 7 provisions. One way of confronting the realization of Muslim objectives, whose fundamental aim is to break down RS via the return of Muslims to their territory and the biological dynamic – is the return of Serb refugees to RS and the promotion of demographic policies to increase the Serb population.

(…) Optimism as regards survival and overall advancement, especially in the socio-economic sphere. This is founded on the fact that RS and its Serb people at this moment, and for the foreseeable future, are necessary to Europe, to protect its interests, above all, in the role of RS in preventing the infiltration of Islamic fundamentalism into the heart of Europe. Also RS has adopted the role of the former Serbian Military Krajina. When the reasons for its existence disappear, our enemies, the Croats and the Catholic Church, will destroy RS if they are in a position to do so, and extend the Catholic borders eastwards

(…) the role of SPC in stimulating measures to popularize the policy is very important, as is the immutable fact of the existence of RS.

Various measures and means of intimidation were used

to prevent Bosniaks from returning to RS in large numbers

The return of Bosniaks to RS is considered the greatest threat to the ethnic consolidation of RS, as was reflected in the reaction of RS towards the returns process. Various measures and means of intimidation were used to prevent Bosniaks from returning to RS in large numbers.

At the same time ‘a radical programme and official personnel changes in the organisation of education, from elementary level to high school, was set in motion, in order to ‘defend the integrity and preserve the consciousness of the Serbs’, and to prevent their ‘assimilation’ into the Bosnian state. In this way, culture and education were placed on an equal footing with the police and army.

Amongst other things, refugee return was the main instrument, as envisaged in the Dayton Accords, to soften the consequences of the war and ethnic division. The international community did not, however, devote sufficient attention to that process on the ground, despite 1997 being proclaimed the year of returns in B-H. Return was realized through the national-ethnic ‘key’, and also consolidated the ethnic division of Bosnia.

Wolfgang Petritsch, the international High Representative in B-H,

succeeded in just one year in changing the situation in the entities

The efforts of the international community to relativise the ethnic division of Bosnia only partially succeeded by means of administrative measures, and in unifying some state functions.

In this manner, the B-H army was unified, and freedom of movement was secured throughout B-H, as well as a number of other concrete issues. RS persistently rejected or resisted the annulling of the state competences of RS. Belgrade at all times openly supported that policy.

Wolfgang Petritsch, the international High Representative in B-H, succeeded in just one year in changing the situation in the entities; in that sense, the New York declaration of November 1999, signed by the Presidency of B-H, was encouraging.

A decision was made on the Brcko enclave, which the Serb side considered a strategic point since it cut RS in half. The government of the FRY (Serbia) protested, insisting that this was

‘yet one in a series of illegal acts on the part of Wolfgang Petritsch, and yet ‘another attempt to impose foreign political and strategic objectives in B-H, against the legitimate interests of RS and the Serb people’.

The Socialist Party of Republika Srpska at that time pledged to arrive at a long-term solution for all refugees to remain in RS. The electoral headquarters of the [Brcko] District committee of that party announced in Zvornik that ‘insofar as Serbs fleeing from the B-H Federation (of whom there were some 400,000) are not retained, and long-term accommodation and perspectives and work found, RS will not survive’.

The introduction of single passports for all B-H provoked a stormy reaction in RS, especially within the SDS, which appealed to all the state organs of RS and the Serb representatives in the joint organs of B-H to adopt a united stand over the decision, which implied annulling the entities on which B-H rested, as well as the Dayton Agreement. The RS Socialist Party also announced that the imposition of

‘such legally binding resolutions will destroy the joint institutions of B-H and lead to the domination and hegemony of one of the three nations of B-H’.

The RS parties also strongly criticised the suggestion of Haris Silajdzic to establish four economic regions in B-H, since that would ostensibly lead to the unitarisation of B-H. In Brcko, on 18 October 2000, there were Serb nationalist demonstrations in the secondary schools, which shouted: ‘This is Serbia’ and ‘Brcko is Serbian’.

The victory of Vojislav Kostunica meant that for the first time

the nationalist bloc achieved legitimacy and international support

Democratic changes in Serbia and RS

Even following the democratic changes in Serbia (2000), there was no change in policy; on the contrary, everything was clearly oriented towards preserving RS.

The victory of Vojislav Kostunica meant that for the first time the nationalist bloc achieved legitimacy and international support. The amalgam of communists and nationalists disintegrated with Milosevic’s defeat, leaving only nationalism which spread and assumed, amongst other things, a strong anticommunist stance and constituted an umbrella for legitimizing the ideology represented by Nikolaj Velimirovic, Milan Nedic, Draza Mihajlovic and Dimitrije Ljotic. Milosevic’s territorial legacy was the starting-point in the establishment of [Serbia’s] geostrategic objectives.

Vojislav Kostunica very promptly demonstrated his priorities in the region. Just days after taking over the FRY presidency, he announced that ‘it is not normal that there are Serb towns abroad’ and that globalists think that ‘the Drina is not a river but an ocean’. On the occasion of the recognition of Bosnia-Herzegovina by the FRY (following international pressure), Vojislav Kostunica announced that the FRY would insist on literal implementation of the Dayton Agreement. He warned that everything ‘which leads to the suppression of the entities will meet with our reasoned and well-grounded criticism’, and that five years after Dayton there was a need for ‘the people to decide their future for themselves’. His announcements, right at the outset of his mandate, demonstrated Belgrade’s position on the division of B-H.

The essentially hypocritical stance towards Kosovo

as an inalienable part of Serbia

had the function of claiming a right to RS

Kosovo in the context of Bosnia’s division

The Serb national ideology after 2000 was nourished by the unresolved status of Kosovo. The Serb war adventure had begun with the idea of amputating Kosovo (due to the impossibility of controlling the Albanian demographic boom), and spreading the Serbian state to the north-west. The essentially hypocritical stance towards Kosovo as an inalienable part of Serbia had the function of claiming a right to RS.

Bosnia’s future, for Serbia, was placed in the context of the resolution of Kosovo’s status, which became a trading tool. When it became clear at the end of 2007 that Kosovo’s status would be resolved within a few months, Belgrade and Banja Luka coordinated their policies and, in the newly arisen situation, initiated a campaign to open the question of RS independence. So the idea of compensating for Kosovo through Republika Srpska came into force in 2007. Vojislav Kostunica in his pre-election campaign in 2007 declared:

‘If we give up Kosovo, then we also give up the right to defend and protect Republika Srpska as a part, an independent part, of Bosnia-Herzegovina’.

Amongst other things, he stressed that Republika Srpska and Serbia were of the same spiritual and cultural space, despite ‘official and unofficial positions’.

The ICJ judgment… led, quite justifiably,

to questioning the legitimacy of the existence of Republika Srpska

The genocide judgment

On 26 February 2007, the international Court of Justice (ICJ) delivered its judgment in the case brought by Bosnia-Herzegovina against Serbia and Montenegro for contravening the Genocide Convention. This years-long dispute, and the judgment itself, reverberated strongly amongst the public in Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro.

The Court, in its judgment, confirmed that in Srebrenica in July 1995 genocide had been committed against the Bosnian Muslims, which was in accordance with the judgments of the Hague tribunal. According to the ICJ, Serbia was not declared responsible for carrying out, complicity or participation in genocide; it was, however, declared responsible for not preventing genocide. Serbia was also declared responsible for not handing over war criminal Ratko Mladic, indicted for genocide and complicity in genocide, to the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia.

The ICJ judgment was received in Belgrade with ‘relief’. Despite the judgment having confirmed genocide in Srebrenica, and Serbia’s responsibility for not preventing it, the political class in Serbia challenged the decision. Such ambivalence in the formulation of the judgment did not merely provoke the dissatisfaction of Bosniaks, but provoked further disputes regarding the character of the war and Serbia’s role in it.

The decision was obviously a kind of political compromise on the part of the international players. The ICJ judgment resulted in deteriorating relations in B-H and led, quite justifiably, to questioning the legitimacy of the existence of Republika Srpska, provoking a sharp reaction from RS politicians.

In the course of 2007, an initiative was launched to divide Srebrenica from RS structures. That is to say, Srebrenica’s municipal assembly adopted a resolution which sought to separate that municipality from RS authority. Serb committee members walked out of the session before the vote on its adoption, with the argument that there was no mandate for destroying the constitutional and legal formation of Republika Srpska, nor for violating the Dayton Agreement. Two truths about the past, with completely different interpretations, the ICJ judgment at The Hague, and deep disagreement about the future of the town, converted a regular session of the municipal assembly into a debate lasting several hours. The then High Representative in B-H, Christian Schwarz-Schilling, stated that the decision on separating Srebrenica from RS was not in accord with the Dayton Agreement.

It was made clear to Dodik that RS independence

was not a matter for discussion

Kosovo independence: a new momentum for Bosnia

The declaration of Kosovo’s independence radicalized the behaviour of Milorad Dodik, and opened the question of the status of RS. Although Bosnia did not recognise Kosovo, unlike all the rest of Kosovo’s neighbours, relations between Sarajevo and Belgrade continue to be tense. Dodik at one point emerged with the request that RS be permitted a referendum on independence. The RS Assembly resolution in February 2008, in which the possibility of a referendum was explicitly mooted for the first time, marked the beginning of a serious new crisis, not only in B-H, but in the region as a whole.

Hidden behind Dodik’s radicalization was the years-long strategy of Belgrade, supported by politicians, the media and the academic elite. In addition, Dodik’s position strengthened the economic ties between Serbia and RS. Reactions to the views of RS politicians were strong, both amongst other politicians in B-H and in the international sphere. It was made clear to Dodik that RS independence was not a matter for discussion.

The destabilisation of B-H once again attracted the attention of the United States and the EU. Bosnia was unexpectedly placed on the priority list of the new American administration, albeit not at the top. Numerous experts at the beginning of 2009 began pointing to the unsustainability of the situation in Bosnia and the possibility of renewed conflict.

Only in the United States was a resolution passed in the Congress; a chain of articles and commentaries appeared in leading US media centres; the Bosniak diaspora in the US strengthened its activities in Congress and the State Department, and a series of Bosniak politicians visited the US. All of this anticipated the arrival of the new administration. In Congress, on 9 April 2009, there was a hearing on which occasion attention was paid to the fact that Milorad Dodik

‘had taken advantage of the international community’s neglect of Bosnia and the deficiencies of the Dayton Agreement which even made RS more independent’.

Attention was also drawn to the fact that Dodik

‘had exploited Europe’s fear of Muslim terrorism in order to avoid any efforts at constitutional reform in B-H’.

It was also emphasized that a new American initiative was essential in order to bring about stability in the region as a whole, especially Bosnia, Kosovo and Serbia. Priority was given to Bosnia, and for the the US administration to complete the Dayton process through initiating a new plan for Bosnian reintegration, but one not based on ethnic principles. It was underlined that ethnic territorialisation works against unity in complex states.

As Daniel Serwer, Director of the Balkan Program at the US Institute for Peace, said:

‘If changes to the constitution of Bosnia-Herzegovina are not seriously set in motion, the international community must consider the holding of a new Dayton. The only theme that should be discussed is that question. No division, separation or similar nonsense.’

Morton Abramovitz and Serwer, in a joint article, suggest a renewed European mediation and US initiative to carry out the constitutional reforms. To start with, the EU and the United States had to state clearly that the current constitutional situation in B-H was unacceptable and must change. If that did not produce results, it would be necessary to convene a new Dayton conference, with the original participants, Croatia, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina with its two entities, as well as the EU, Britain, France, Germany and Russia. After consultation with all participants, the United States and the EU should prepare a draft for a new constitution which would meet European standards.

In the course of 2008, three events took place in Bosnia-Herzegovina which were of historic significance there.

The first was the capture of Radovan Karadzic in Belgrade in July. Although it took place on Serbian territory, his capture was of particular importance for B-H, for at least two reasons. First, Karadzic is being tried at The Hague for war crimes and genocide, not only in Srebrenica but in 11 municipalities throughout Bosnia.

Additionally, General Momcilo Perisic is also being tried in The Hague, according to the indictment, through his position as the Chief of Staff of the Yugoslav Army in founding the so-called officers’ centre, which was responsible for financial and logistical assistance to the Army of Republika Srpska, for carrying out their orders to army chiefs. In this way, according to the indictment, Perisic from the middle of 1993 to the end of 1995 contributed to the atrocities in the siege of Sarajevo, the shelling of Zagreb and the fall of Srebrenica. Both of these trials (Karadzic and Perisic) play an important part in bringing to light the role of Belgrade in planning and carrying out genocide in Bosnia.

The second event was the signing of the Stabilisation and Association Agreement between the EU and B-H: the Agreement was signed on 16 June 2008 in Luxemburg. In parallel with the SAA, a Temporary Trade Agreement was signed which marked – as was stated in the conclusions of EU state and government leaders – ‘an important step for B-H along the road to the EU’. The signing of this agreement was made possible following reforms of certain segments of the joint state: ‘reforms’ of its policy, public administration and public RTV services.

The attempt to find a solution within Bosnia – the Prud Agreement between the leaders of the political parties (Milorad Dodik, Sulejman Tihic and Dragan Covic) – did not secure the full support of the Bosnian public. Essentially, the real content of the Prud Agreement was never disclosed; but from the declarations of the three leaders it was possible to conclude that there was, inter alia, discussion of the creation of a third entity with its headquarters in Mostar, and a division of state property the beneficiaries of which would be the entities.

That attempt failed, despite support from the international community. The High Representative, Valentin Inzko, also confirmed that

‘I support all that the three peoples do willingly, such as the Prud process. It would be good if the other parties joined in. This is not the only condition for closing the OHR, or for its transformation, but it would be a sign of maturity.’

The European Parliament passed a resolution on B-H which sought the formation of a functional state and institutions, in order to accelerate the process of EU integration. Evidently, the failure of these talks also prompted the renewed internationalisation of the Bosnian issue.

However, the international community allowed Dodik to continue with the process of weakening the unitary state, which further distanced B-H from the European perspective.

The only positive medium-term strategy in relation to Bosnia was adoption of the Bonn Powers for an extended period. The RS position within B-H also became redefined during this time. In the longer term, a serious revision of the Dayton Agreement will be essential, as this is a stumbling-block in the process of consolidating the state.

The possibility of restoring genuine relations between Serbia and B-H

will only be realized if Belgrade relinquishes its practice of destabilisation towards B-H, and officially and formally apologizes

to the victims of the Bosnian war and their families

Redefining relations within BH remains the first precondition for development of the country. The possibility of restoring genuine relations between Serbia and B-H will only be realized if Belgrade relinquishes its practice of destabilisation towards B-H, and officially and formally apologizes to the victims of the Bosnian war and their families, in a responsible manner. In other words, it will be impossible to heal relations between Serbia and B-H in a meaningful way until the Serbian political leadership demonstrates in an honest manner its remorse for atrocities committed in the 1990s. The policy of aggression and ethnic cleaning which resulted in the murder of over 100,000 people, tens of thousands of cases of rape, and the displacement of more than 2 million people, has never – at least formally – been adequately condemned in Serbia, or by the RS parliament, president or government. Moreover, on the question of concrete material compensation, there has not been even a word.

Belgrade and its neighbours

The main problem is Serbia’s relations towards its neighbours and its desire to maintain patronage over them. Even two decades after the fall of SFRY, today’s political leaders still do not comprehend the context of European regional cooperation and, in that sense, the meaning of ‘European perspectives’.

One of the key directions of Belgrade’s activities in the region is linked with the population census which is scheduled to take place throughout the region during 2011, on the occasion of which the Ministry for the Diaspora introduced a Strategy for Preserving and Strengthening relations between the motherland and the diaspora, and the motherland and Serbs in the region, which is viewed in the region as a miniature Memorandum.

This strategy has been in process for three years, with numerous institutions and individuals contributing to the document. The Minister for the Diaspora has stressed that

‘no longer will our people in the world be treated as political opponents, and Serbs in the region will no longer be misused for daily political purposes. We must all contemplate the fact that 40 per cent of our people live outside our national borders, we should draw lessons from the past, and we should never again allow in Serbia the dominance of a policy which encourages people to leave the country.’

The Strategy stresses that it was the intention of the Republic of Serbia to assist the diaspora and Serbs in the region, on the one hand to integrate into local areas and, on the other, to resist assimilation; and that on that question close cooperation with the Serbian Orthodox Church was expected. With the fall of the SFRY, Serbs who had been constitutive peoples had become minorities in the newly formed states.

The Strategy seeks that Serbs in Croatia and Montenegro should once again receive the status of a constitutive people. Due to the reaction in Montenegro and Croatia, the bid for such a status was abandoned. It was alleged that in neighbouring states the Serb communities have been disenfranchised, and in certain quarters the minorities have not been guaranteed international standards and basic human rights, freedom of movement, schooling in their native language, employment, and so on.

In relation to Republika Srpska, the Strategy stresses that RS should represent the most important area of interest, as one of the state and national foreign-policy priorities of the Republic of Serbia… It is further stressed that the relevant ministries should permit all citizens of Republika Srpska who so wish to obtain Serbian citizenship. The Republic of Serbia

(…) should insist on consistent implementation of the Dayton Agreement and continuous empowerment of Republika Srpska and its institutions. The Foreign Ministry should, in every way, diplomatically support efforts for the survival of Republika Srpska, and defend its rights before the EU, the USA, the Council of Europe, the OSCE and the UN.

It stresses that the Ministry for Economic and Regional Development should encourage investment into districts in Republika Srpska, especially in zones with little growth (Herzegovina, Podrinje, Manjaca) and zones of vital strategic importance (Brcko, Posavina, the Una valley).

The Ministry of Education should continue the process of unifying the two educational systems. The Ministry of Culture should devote considerable attention to the cultural advancement of the Serb people in Republika Srpska and its ties with the motherland.

The Ministry of Religion should continue concern for – and the financing of – priests and monasteries, bearing in mind their spiritual mission in protecting the national identity, offering assistance to religious, cultural and educational institutes, publishing projects, radio and TV stations, and the restoration and renewal of the sacred heritage of the Serb people.

The Strategy also addresses the position of the Serb people in the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, starting from the point that all Serbs are a constitutive nation in that entity, but also bearing in mind their unfortunate position vis-à-vis Bosniaks and Croats in Republika Srpska.

The Strategy holds that the relevant ministries in the Republic of Serbia, alongside their normal activities, should help the return of Serbs to – and their economic survival in – Bosnia-Herzegovina. In short, the Republic of Serbia supports the restitution of property taken from Serb citizens, Serb societies and institutions (banks, savings banks and cultural-educational companies) as well as the Serbian Orthodox Church; the restoration of the sacred heritage of the Serb people; the development of educational centres and the Serbian Orthodox Church (seminaries, secondary schools, primary schools, nurseries, etc).

Republika Srpska is becoming increasingly confirmed and cemented as a war booty which Serbia will not give up.

This was also referred to at the recent international conference in Sarajevo by Goran Svilanovic (May), when he quoted one Serbian politician who, on the question of what was the result of supporting the Milosevic project and nationalist policy, had answered: Serbian Vojvodina and Republika Srpska.

Svilanovic said:

‘In defending these results, Serbian national opinion is far more united than might be apparent, despite what Goran Svilanovic or anyone else who comes to Sarajevo may say. The honest answer to the question of whether those are the results which this and any future government of Serbia endeavour to protect, the answer is – yes.

‘Secondly, and more unpleasantly: my impression is that it is important to say in Sarajevo that the constitutional patriotism amongst citizens (not politicians) of Republika Srpska is almost equal to zero in relation to the state of B-H.’

the exchange of Kosovo for Republika Srpska is not possible,

and therefore it is important that Belgrade finally sends a clear message

to the citizens of Republika Srpska

that Bosnia-Herzegovins is their country, not Serbia

The role of Belgrade in normalizing relations within Bosnia

The normalisation of relations within Bosnia-Herzegovina will not be possible in the longer term while Belgrade persists with its imperialistic pretensions in the region. In other words, the exchange of Kosovo for Republika Srpska is not possible, and therefore it is important that Belgrade finally sends a clear message to the citizens of Republika Srpska that Bosnia-Herzegovins is their country, not Serbia.

The resolution of Bosnia-Herzegovina’s problems depends on the constructive role of Serbia. The influence which Serbia has on politicians in Bosnia can be of crucial importance for the development of events. And if Serbia wishes to speed up its path to the European Union, its behaviour towards Bosnia will be particularly important.

the Bosnian question is still open,

due to the lack of political will to approach the issue

also from the moral standpoint

Belgrade’s continual insistence on the status quo and on the immutability of the Dayton Agreement, and on the mantra that Belgrade will accept everything ‘which is agreed on by the three groups’ speaks more about the weakness of Europe than the strength of Serbia.

Serbia rose on the support and help of the EU and US, and its policies and blackmailing powers are the consequence of the weakness of the West to resolve some fundamental questions which are not local in character.

The arrest of Ratko Mladic could assist in a new international initiative in Bosnia. At the same time, Serbia’s candidature, and the start of negotiations for EU membership, would certainly reduce Serbia’s support for RS. This would also imply the orientation of RS towards Sarajevo as its centre.

Consequently, the Bosnian question is still open, due to the lack of political will to approach the issue also from the moral standpoint. Bosnia was, and remains, a moral issue for Europe. It is finally time for the international community to adopt a position in relation to the crimes which have taken place against Bosnia and the Bosnian people. It is immoral that Srebrenica remains in the Serb entity and that the killers and persecutors walk around in the streets of that town freely. When the Mothers of Srebrenica are no longer around, that town will be not only a town of the dead, but a dead town. Srebrenica is a symbol of atrocity, and of the insensitivity of the world, especially Europe.

The Declaration of the European Parliament is an important document, therefore, which returns to Srebrenica in an attempt not to forget that atrocity. Finally, Europe treats that atrocity as its moral responsibility. Nation-building in Bosnia must be set on new foundations where the citizens are the central focus. The Bosnian Serbs must be helped to free themselves from the exclusive responsibility for genocide that Belgrade has foisted on them, because that will place a lasting wall between them and the Bosniaks. And, finally, reconciliation in Bosnia will be possible only based on the truth, and not on the equalisation of all three sides.

In the completion of the Balkan mosaic, Bosnia is the last piece. It is also the place in which the most errors were made. It would be useful for Europe to acknowledge some of its own blunders and errors. It would help the region itself to act more responsibly in relation to its recent history.

The first official visit of Boris Tadic to Sarajevo and Bosnia-Herzegovina at the beginning of July 2011 could mark the beginning of a new policy of Belgrade towards Bosnia.

[…] More eg in Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state […]

[…] Ari RUSILA: Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state […]

[…] in criminal activity – including heroin trading – since before the 1999 war. More e.g in Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state and Captured Pseudo-State Kosovo […]

[…] Kosovo: Two years of Pseudo-state and […]